Quick overview

Classical Echoes – 16 October 2024

Quick overview

Just like Isaac Newton is for physics or Homer is for poetry, Johann Sebastian Bach is a key figure in classical music — and in music in general. He’s the man who shaped music as we know it today and ended up inspiring generations of composers, from Mozart and Chopin to Joplin, the Beatles, and many others great musicians.

During his lifetime, Bach wrote over a thousand pieces, covering almost every genre of his time (except opera) while staying within a 200-kilometer radius his entire life. Yet, when comparing J. S. Bach with the soft and dreamy Chopin, the dramatic and epic Beethoven, or the cheerful and perfectionistic Mozart, Bach’s music may seem repetitive, monotonic, sometimes harsh, and, well… quite boring.

In this post, I’ll try to break down what Bach’s music is all about, how to understand it, and hopefully, how to LOVE it.

Born in Eisenach, Germany, in 1685 into a family of musicians, Bach’s father taught the young boy the basics of musical theory and how to play several instruments. Both of his parents died when Bach was 10 years old, leaving him and his siblings to fend for themselves. He was forced to move in with his elder brother, who was an organist at St. Michael’s Church. There, young J. S. learned from his brother and other musicians, developing his own musical tastes and principles that would enhance his musical style in the future.

During his youth, he was introduced to the works of great German, French, and Italian composers, including J. Pachelbel and J. B. Lully, whose music deeply inspired him. He also studied different languages and theology, which fostered a strong belief in and connection to God—a cornerstone idea of his music that would later be reflected in his timeless works.

In the halls of churches, Bach encountered the instrument that became central to his life: the organ. He dedicated countless pieces to it, including famous fugues and toccatas. Bach’s use of the organ was so modern and awkward for the time that he was often criticized for his exaggerated improvisation during church masses.

Eisenach (Germany) – a house where J. S. Bach was born in 1685

While many listeners associate late Baroque music with Vivaldi’s ‘bangers’ and (of course) Canon in D, almost all of Bach’s works, from the simplest to the most complex, are characterized by counterpoint structure. It’s a technique of combining two melodies played simultaneously, creating a unique harmony that splits your listening focus.

The most obvious example of counterpoint, the fugue, is a relatively short piece where the main theme is introduced at the beginning, accompanied by a countersubject to build a complex harmony. Usually, new themes (subjects) are introduced as the fugue develops, combining themes into stretto, where many of them are played at once.

It may sound easy to just combine two simple themes and play them throughout the piece. However, the reality is more complicated, and creating a meaningful contrapuntal piece is a much harder task, requiring imagination and deeper exploration beyond just writing simple polyphony.

Undisputedly, Bach was a master of counterpoint. Listening to his works is an intellectual challenge because following every voice and keeping track of all the themes requires not so much music theory classes, but actually paying attention and following the lines.

The reason why Bach didn’t write any operas (or other ‘shows’ of the time) is that his focus was purely on the music, unlike his predecessors, like Monteverdi, for example. He didn’t even need meaningful text for his cantatas. It’s okay to listen to the Mass in B Minor, where every part is just repetition of “Kyrie eleison” or “Confiteor unum baptisma in remissionem peccatorum” without understanding the meaning of the words, because Bach expressed all his thoughts through the abstract meaning of his music.

He loved experimenting. With any awkward or silly theme given to him, he could compose astonishing three- and even six-part fugues, (referring to The Musical Offering).

His exploration of music and experimentation were considered so incomprehensible that Bach was considered as an old-fashioned composer even during his own time, as high society preferred more relaxing and light music.

A famous Crab Canon from musical offering. A palindrome that can be played vice versa. (yt: Jos Leys)

Let’s be honest, we often associate classical music with the ideas behind it, its expression, and the emotions of its composers. Try to imagine the most beautiful, soul-touching piece—perhaps the first that comes to mind is one of Chopin’s nocturnes or Schubert’s lieder. It might also be associated with a more structured and perfect form, like Mozart’s serenades or Beethoven’s early sonatas.

On the other hand, Bach’s music, as well as most Baroque music in general, doesn’t seem to make you fell some particular emotions like clear joy or sadness. In Bach’s case, his music may sound monotone and follows a strict structure with multiple movements and overcomplicated melodies.

The main reason people think Bach is boring or outdated is that we don’t appreciate his genius in the right way. Listening to his fugues, partitas, or any major piece is an intellectual pleasure. It’s like reading a really profound scientific essay or listening to a mesmerizing conversation between two geniuses. If you don’t pay attention, you quickly lose the thread and get bored.

The same thing happens with Bach’s music. In his complex works, often with multiple voices and subjects, he creates a clear line for you to follow. He doesn’t include interruptions or tempo changes, and the more carefully you listen, the more hypnotizing the “Bach effect” becomes.

So if you decide to listen to Bach while making dinner or walking your dog in the park without paying close attention, you’ll quickly get bored and think of him as just a guy who wrote piano exercises for conservatories.

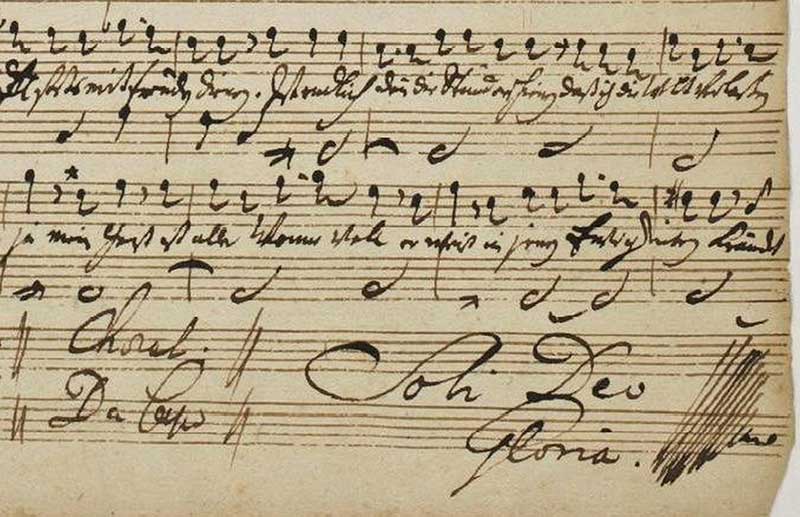

Soli Deo Gloria (SDG) – a signature that Bach left at the end of many of his pieces, meaning “Glory to God alone.”

Throughout his life, J. S. Bach was deeply connected to God and the Protestant religion, in particular. He composed countless works for church services and simply to praise God.

He believed that music was a gift from the heavens, and that he was a transcriber of Father’s words through music.

In his works, he tries to explore all corners of the universe, building perfect harmonies and creating a deep spiritual experience for the listener. His religious mentor, Martin Luther, who was also a musician, declared music to be the second only to the gospel itself. Unlike more traditional Orthodox or Catholic churches, where music was produced only for services and adhered to strict rules and structures, Lutheranism allowed Bach the freedom to develop, experiment with different techniques, and compose more complex works.

SDG signature by Bach

Perhaps the most famous organ piece by J. S. Bach, often used for its iconic opening in the toccata section (Dracula’s theme). It is also one of the most controversial and mysterious of Bach’s works due to its power and emotional depth, which is uncommon for the sophisticated and conservative J.S.

The exact date of when Bach wrote the piece is unknown and varies between 1703 and his death in 1750. It was probably written during his early years as an organist in Arnstadt, influenced by the series of tragedies and losses in Bach’s life following the consecutive deaths of his siblings and parents. Or in his mid-thirties following the unexpected deaths of his first wife and children.

There are also doubts that Bach himself wrote the piece. Some scholars believe it was composed by one of his students and later dedicated to him. Its extraordinary dark and powerful nature, as well as its ‘simplicity’, according to Bach’s standards, particularly in the Fugue, adds to the mystery behind the piece. However, the fugue section resembles more of a fantasia and carries a deeper intention that the composer put into it.

This piece may become the most profound, thrilling, passionate, powerful, or, simply, greatest musical experience for you, especially when listening to a complete version live somewhere in a Lutheran church concert. Its scale and epic effect on the listener can be compared to beasts like Beethoven’s or Mahler’s symphonies, Rachmaninoff’s piano concertos, or Vivaldi’s Four Seasons.

Toccata and Fugue in D minor by J. S. Bach (yt: MovieMongerHZ)

The Brandenburg Concertos are a series of six orchestral pieces published in 1721 and dedicated to Brandenburg’s military nobleman, Christian Ludwig. Though the work was first presented in 1721, it may have been composed earlier. This is regarded as one of the greatest orchestral works of the Baroque era, and one of the most important works of Bach’s middle period.

Around 1719, Bach played for Christian Ludwig, who was impressed by his talent and asked him to compose something for him. It took Bach two years to send what we now know as the Brandenburg Concertos. Despite all agreements and the astonishing work, the Margrave never paid him. One possible reason is that these pieces weren’t new—Bach had actually reworked music he had written earlier for the court at Köthen, which the Margrave may have known.

Each of the six works consists of three movements, with a duration of about 20 minutes, and features one or several main instruments accompanied by the rest of the orchestra. Here, Bach develops his use of counterpoint and builds perfect harmonies, speaking through each instrument and voice to bring new ideas. It includes some remarkable moments, like the harpsichord cadenza from the fifth concerto, which was an uncommon practice at the time.

The Brandenburg Concertos may be the finest example of what great music sounds like, and what often comes to mind when discussing Bach. Their light and joyful nature, along with the “lines” Bach builds, create one of the most mesmerizing musical experiences.

J. S. Bach – Brandenburg Concertos (yt: ClassiclaVibes)1

A titanic, epic work for chorus and orchestra, with the purpose of praising God and His creation, it is regarded by many, including Bach himself, as his life’s work. It is an extension of an earlier mass written by Bach in 1724, which he later expanded with additional sections and movements.

The piece is gigantic in every sense. With a duration of around 2 hours, Bach tried to introduce every musical style, making it a benchmark for all of his works. Bach completed three different sections of the work throughout his life, but he did not title them Mass in B Minor. Instead, he organized them into one folder and named the sections separately, as many of the movements are not actually in a key of B minor.

The work had a particular meaning for J. S. Bach, reflecting his deep religious feelings and his glorifying God only. Since he wasn’t hired by a church or some king to write the piece, he had the freedom to work on it at his own pace, rewriting and changing each part. This is why the piece contains many examples of his finest canons and arias, use of multiple voices and counterpoint, like in Confiteor fugue.

Bach assembled and completed the work in 1749, a year before his death. Due to its big scale and complexity, it was difficult to perform at the time and wasn’t played during Bach’s life. It wasn’t performed in its entirety until the mid-19th century, with the first full performance in Leipzig, Germany, in 1859.

This is a masterpiece that everyone should listen to at least once in their life. Sit through it and try to get Bach’s genius—it may become one of the most mesmerizing two hours of your recent memory.

J.S. Bach – Mass in B minor from BBC Proms of 2012 (yt Mandetriens)

One of the most well-known of Bach’s works and essential for all piano students, the first book was completed in 1722 and consists of 48 pieces in total, with 24 preludes and 24 fugues for all possible keys (except A-flat minor). Written for a specific instrument, the clavier (or simply a keyboard), it had the special purpose of helping with tuning and exploring the sound of each key. Bach dedicated it to students learning the keyboard as well as to those already familiar with the fundamentals of harpsichord playing. Twenty years after the first edition, Bach wrote WTC2 with the same structure and purpose.

Despite being a purely functional musical work, meaning it had the specific goal of helping to tune and explore all keys, it remains a profound cornerstone in classical music. Every major composer after Bach learned composition techniques and played through the WTC.

Its short and, at first glance, simple preludes and fugues may seem easy and don’t have the immediate impact of Bach’s more famous works. However, this is a true masterpiece that shows Bach’s genius. The beauty of this piece lies in its simplicity—an idea of telling a story and implementing genius ideas through music and sound.

Some believe the entire work represents the life of Christ, depicting stories from the Bible, like his journey to Egypt. It includes simpler fugues as well as some of the most complex in history, such as the C# minor fugue from WTC1 or the B-flat minor fugue from WTC2.

It makes sense to explore this piece with sheet music in hand, finding patterns and meanings in the sounds, such as the depiction of birdsong in the prelude in G minor.

G. Gould plays WTC I (yt. vermann)

Glen Gould – Art of fugue (yt. glengould52)

See also: