Quick Overview

Alfred Brandel – a Chezch born Austrian pianists and musicologist. One of the most reowned pianists, famous for his Schubert, Beethoven and Mozart.

See Also

F. Schubert: Sonata no. 21 – Complete Guide

Classical Echoes – 29 November 2024

Schubert's sonata no. 21 in B flat major – complete guide and overview of the great masterpiece

Quick Overview

F. Schubert is one of the most loved composers of all time. However, shadowed by the great and more famous Beethoven, the Austrian young musician didn’t receive as much attention as he does now and lived his short life mostly in poverty and loneliness.

He was known more as a simple songwriter. Nevertheless, in less than 20 years of his career, he was an incredibly prolific composer, writing in almost every possible musical style, from piano impromptus and lieders to symphonies and operas.

To be honest, Schubert never experienced great fame like Beethoven and Mozart during his life and wasn’t treated fairly in terms of his works, some of which are truly genius. Most of his masterpieces were discovered and published by the next generation of romantics, including Mendelssohn, Liszt, and Brahms.

In light of this, it is reasonable that his piano sonatas—21 of which he wrote during his life—didn’t get much attention compared to Beethoven’s, for example. At the end of his short life, understanding that he was ill and nearing death, Schubert wrote some of his greatest works, including the last three piano sonatas. They are believed to be interconnected and derived from each other.

In this post, we will discuss his last sonata, the greatest, longest, most profound, and most beautiful of all: Schubert’s Sonata no.21.

Introduction

The year is 1828. Schubert, ill and weak, is living alone in Vienna. His financial situation isn’t good, and he knows that death will soon knock at his door. Despite this, his final years are among his most prominent and active as a composer. He publishes some of his greatest masterpieces, such as the String Quartet Death and the Maiden and his last symphonies, including the 8th (Unfinished) and the 9th (The Great). These works finally start to bring him more recognition and improve his financial situation.

As a result, he performs his last three sonatas (D. 958-60) in Vienna only two months before his death, including the final Sonata in B-flat major. The public appreciates the sonatas for their complex structure and beauty and begins to recognize Schubert as a more wide-ranging composer. This peak in his career may have been influenced by the recent death of Ludwig van Beethoven the year before, which made Schubert one of the greatest composers alive in Vienna. Despite this final burst of fame and the beginnings of a more successful life, Schubert was feeling sick and desperate. He was anxious and afraid but never lost his faith. He always tried to stay alive and do what he was born to do in this world: to write wonderful music. This feeling is best expressed in his final Sonata No. 21, one of Schubert’s major and most beloved works. It is widely considered one of the greatest sonatas ever written and one of the most beautiful piano pieces. Yet, it is deeply personal and sentimental when you realize the main message of this piece.S. Richter performs Schubert’s sonata no. 21 in B flat Major (yt. incontrario motu)

I. Molto Moderato

The first movement of the Schubert’s 21st Sonata is the longest of any movement in Schubert’s piano music and a cornerstone of the entire sonata. It takes about 25 minutes to perform and consists of numerous mood and sound changes.

The movement is marked Molto Moderato (very moderate) and focuses on deep musical meaning hidden within its main themes. It demonstrates how a composer can tell a meaningful story through sound, evoke a wide range of emotions, and make the listeners portray the sound in their minds. The first movement begins with long, lovely ligato chords in the B-flat major scale. It introduces a pleasant melody, almost like a song, creating a feeling of calm and peace. Suddenly, instead of a meaningful ending of the theme, Schubert shifts the melody into indeterminacy, changing the pleasant mood of the opening. After a moment of silence, a quite unexpected trill in the left hand on the G-flat major completely changes the ‘direction’ of the piece.

Sonata no. 21 – opening (free sheet on Musopen.org)

The opening sets the mood for the sonata, where the pastoral tune at the beginning can be interpreted as an old man’s life, nostalgic dreams, and reflections on the past. Meanwhile, the trill symbolizes fatigue and weariness—perhaps death. Hungarian pianist Andras Schiff siad that this is “The most important trill in music.” Later, we will understand why this is a key idea of the entire sonata.

This interpretation reflects Schubert’s late years. Finally gaining some recognition and fame as a composer, he is aware of his illness and understands his death is near. The trill in the left hand was a common technique used by Schubert—for example, in Impromptu No. 3—to represent some anxiety. The theme reappears again with a different tone, ending with a similar trill, now on B, flowing into a more vivid melody, also a variation of the opening. After a beautiful modulation, the main subject bursts into a joyful, almost hymn-like melody with repeated notes in left hand as an accompaniment. After this, the theme is lost in a series of tonic chords, which brings the sonata into an unexpected F-sharp minor turn. The mood becomes more dramatic and dark. It’s unclear whether the melody in the right hand doubles or the descending notes in the left hand, picturing a feeling of despair and no escape. The mood moves again into a more prominent A major, with some melancholic progressions in B minor, after which a third section returns to the main key of B-flat major, playing descending and upscaling open chords.

Exposition of First Movement

The interesting part of the exposition is its final section, where the uncanny melody, almost like a dance, interrupts with gentle arpeggios. This weird Schubertian musical statement shows the vague nature of the first movement (and the sonata in general), where the protagonist is faced with some unresolved problem that follows him along despite the moments of abstract joy and happiness.

Finally, we hear haunting leaps in the left hand, followed by quiet A minor answers. This repeats once more after it bursts in loud F-dominant chords in the “Fate rhythm” from Beethoven’s 5th, followed by a fortissimo left-hand trill from the beginning—the only time in the entire movement when we hear it so emphasized.

After a long and terrifying silence, the huge exposition repeats again. We will hear the main theme, including opening B-flat chords and the trill in the left hand, later in the movement, with different variations. After Schubert presents the key idea of the piece described in the exposition, the narrative continues in the second part, the development.

The final trill in exposition

The development section begins with a similar theme, now played in C-sharp minor, a tragic and sorrowful key. It becomes lighter with the entry of progressive arpeggios, similar to those in the exposition. After harmonic transcending, it returns to B-flat major, introducing the second section.

It begins with a repeated note in the left hand and a basic melody in the right, which reappears a second time, now in A minor, flowing into E major, a relative major of C-sharp minor. The melody then shifts into the left hand, and in the right hand, we hear crescendo semitones that have an eerie feeling. After the long modulation at molto crescendo, the music bursts into breathtaking D minor perfect cadenzas played at fortissimo, creating a stunning sound effect. The climax then interrupts, and we hear only repeating D minor chords, which sound like an echo of the previous storm. The third section is introduced. The third section of development is probably the most haunting and mesmerizing part in all of Schubert’s 21st sonata. Here, the composer creates an extraordinary feeling using the simplest melody and musical techniques. The magic is created by the gentle D minor chords and melody in the right hand that flows constantly from minor to major, creating this effect. It is repeated then in the left hand with a slight variation in sound, with beautiful modulations from D minor to F major. Then the variation of the main theme and trill is repeated—the first time we hear its melancholic variation in D minor, secondly in B-flat major. The transition D–B-flat–D may seem simple musically but creates the effect Schubert tried to describe to us, both haunting and enchanting, almost hypnotizing. After exiting this miraculous state of unconsciousness, the development section ends on the G-flat trill in the left hand, after which—a silence comes. You could have just noticed what an important role the fermata after the trill plays. A terrifying and uncertain silence gives a moment to rethink what will be next. After this, the recapitulation begins.

The enchanting part of the development

The final part of the first movement opens with the same main theme from the beginning: the melody in the right hand, B-flat chords, followed by the trill again. The music then develops similarly to the exposition, but suddenly we hear a familiar shift from B-flat to F-sharp minor. Unlike in the first part, the melody has an additional melancholic turn, adding that feeling of anxiety in the air.

The melody then transitions to relative A major and bursts again into the main theme with precise repeating notes accompaniment in the left hand, like in the exposition. We will not discuss further the recapitulation section, as for the most part, it is a repeat of the exposition in a different key with some new elements and ornamentation. Though it was common practice for the classical sonata structure, it may seem quite disappointing that Schubert in his sonata decides to maintain the third part of the first movement so similar to its exposition. Nevertheless, we hear again the main ideas of the entire sonata and come closer to the closing of the huge first movement, the most important of the 21st Sonata. The movement comes to the end with a new section with some interesting progressions unheard before. The final thought of the protagonist before the meaningful conclusion of his journey. Finally, we hear a gentle and beautiful coda, with chords from the main theme. They clearly picture the end of such a beautiful story, leading to a peaceful ending. We hear the last descending trill on G-flat, and after this, the melody comes to the end with final B-flat chords… We now need to explore the further conflict demonstrated in the first movement.II. Andante Sostenuto

The second movement is the darkest part of Schubert’s piano sonata and plays a crucial role in the development of the abstract conflict shown in the sonata. It is relatively shorter than the first movement and represents the state of transition of the character. It is marked Andante Sostenuto and starts in C-sharp minor, with the same marking and key as the famous first movement of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata.

Indeed, there are many similarities and references to Beethoven’s music. Schubert’s Sonata No. 21 is believed to be inspired by Beethoven’s Hammerklavier: they both are written in B-flat major and have similarly grandiose sizes. However, these are completely opposite pieces in their nature. While Beethoven demonstrated his late-life struggle in a dramatic and more philosophical approach, Schubert, being more romantic than a classical composer, chose a completely different nature. Nevertheless, the second movement of Schubert’s sonata opens with dark C-sharp minor chords, accompanied by octave leaps on C-sharp in the left hand. This makes it sound like a funeral march, with a dark melody. The leaps in the left hand change from C-sharp to G-sharp, and the melody starts to crescendo and progresses further into a louder and louder culmination, ending with the final leap in the left hand. We hear the main theme of the movement in different variations further on.

Sonata no. 21, Second mov. (opening)

After this dark entry, we hear the theme now played in a more joyful and prominent E major, which reminds us of sun rays appearing from clouds, bringing a little bit of hope and relaxation. The melody flows similarly to the opening with slight variation but then transitions back to the home key of C-sharp minor—the clouds come again and close the sun. The ppp chords represent the quiet tears of the main character, being desperate and sorrowful, seeking some hope in his life.

The moment of hope comes in the second part of the second movement, now in A major, which is a much more joyful and pleasant melody, completely opposite to the beginning. It is a more active and vivid theme, where the left hand creates an accompaniment for the main melody in chords, similarly to the first movement of the sonata. The theme repeats in different variations again but doesn’t have a meaningful or expected ending. Instead, it flows back into C-sharp minor.

Second movement – second part

Schubert introduces the main theme of the second movement again in the recapitulation, but now in a different variation, making an accent on the left-hand descending notes. It creates a contrapuntal sound, where the low notes are now more enhanced, reminding the trill from the first movement. The melody is now in the rhythm of a funeral march again, slowly flowing and fading away into the conclusion. The movement ends on a sad note and long silence with the expectation of what’s next.

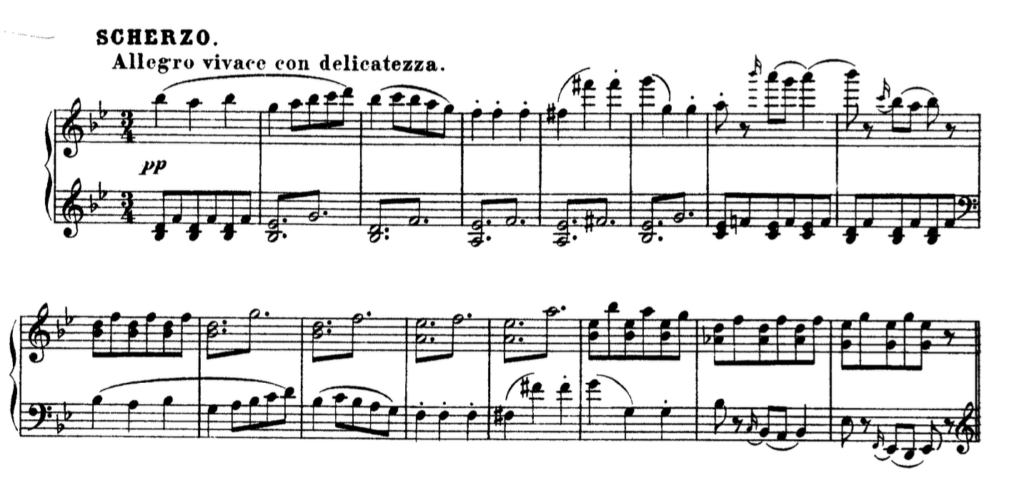

III. Shcerzo. Allegro vivace con delicatezza

The Scherzo movement of Schubert’s sonata is a transitional part between the previous statements and the final anagnorisis. It is often ignored by listeners as an unimportant movement compared to others; however, there are many interesting things about this part despite the beauty and simplicity of it.

In the 3rd movement of the 21st sonata, we see the main argument of the relativity of the Schubert’s sonata to Beethoven’s Hammerklavier. Particularly, it has many similarities to the Scherzo from Beethoven’s sonata, where it plays the same role of being a transition between movements. They both have the same structure: B-flat – B-flat minor – B-flat.

The main theme of third movement of the sonata

In Schubert’s sonata, the movement starts with a playful and catchy melodic theme in B-flat major, the true definition of Scherzo, literally meaning “joke.” The B-flat major theme changes its tone to G minor, making this a more gloomy but amazing variation. After the repeat, the melody slows down, and we hear a more melancholic second subject with a similarly remotely related shift from B-flat to F-sharp minor. After this, the main theme recapitulates in a beautiful and fast coda.

After the short introduction, the Trio part of the third movement begins. It has the same key as in Hammerklavier and the same mood change from a vivid melody to a more dramatic and dark turn. It begins with a slower chord melody in B-flat minor, with accents in the left hand, which builds a double melody. It then transitions into D-flat major, creating one of the most beautiful sounds in the entire sonata, after which the Trio theme repeats in different variations for about 12 bars.

The movement comes to an end with the same theme as it opened, repeating the playful and life-affirming melody, which makes a big contrast with the dark second movement. Finally, the Scherzo part ends with three gentle, quiet B-flat major chords. However, the solution to the story isn’t resolved yet, and we are nearing the final, fourth movement of the sonata.

IV. Allegro ma non troppo

We now land on the final fourth movement, the recapitulation of this whole story pictured previously in the sonata. Here’s the final resolution and many details to keep attention on, as it is the most active in mood changes movement in the whole sonata.

It smoothly passes from the Scherzo part and starts on a loud G octave. This is followed by a very dancy and catchy melody in G minor. A really simple and memorable theme, showing what a great melodist Schubert was.

Sonata 21, IV mov. – main theme

The G octave at the beginning here plays a crucial role, like a trill in the first movement. It is a common signature in Schubert’s music. For example, the Impromptu No. 1 in C minor starts similarly with a long loud G octave, an enormous introduction. This pattern comes from his earlier famous work, Der Erlkönig, based on the tragic poem by Goethe, where it opens with loud repeated octaves on G, representing the gallop of the horse and a deeply anxious feeling of death and darkness.

After beautiful variations of the main theme, the music flows into the second part with amazing and enchanting progressions, consisting of gentle broken chords that flow like waves on the ocean, a state of acceptance and peace for the main character.

This beautiful passage slowly fades out and disappears without a clear ending. After a short pause, loud and violent C minor chords burst, flowing into a dramatic and furious theme, an extremely unexpected turn Schubert made. The state of calm was interrupted by an enormous feeling of fierce and desperation. The dotted rhythms and loud chords in C minor sound like thunder, but suddenly the octaves in the right hand begin to calm down, and the second, much more quiet and peaceful variation in B-flat major enters.

After this fierce and tragic moment, the main theme from the beginning repeats again. Notice the contrast between the G octave and the lively melody after. While the octave represents the main antagonist in the sonata, the theme after it is completely opposite. Schubert shows that he doesn’t care anymore or doesn’t want to care about death and mocks it in this funny melody.

The rest of the movement is mostly a repeat with some new elements that enhance the main ideas of it. The sonata slowly comes to the end, the final statement which will decide the whole idea of the sonata and make a final conclusion.

Lastly, we hear the main theme but suddenly interrupted by the octave, now played in different notes. It slowly descends from G to G-flat and finally to F. The theme quiets and ends for a moment, followed by an uncertain silence in expectation of the huge finale of this enormous philosophical sonata.

The finale begins with loud octaves similar to the previous part in the last movement but now in a much more triumphant key of B-flat major, which represents the victory of life over death—a truly glorious finale that finally resolves the conflict of Schubert’s sonata, bringing us to a positive conclusion.

It now becomes clear that the main idea of the sonata was a victory of life over death—a light in a place full of darkness, where the main antagonist, despite his despair, finally comes to terms with, at first glance, a hopeless situation and shows his strength to withstand even the toughest circumstances. This brings even more poignancy, knowing that Schubert passed away just six weeks after completing his 21st sonata, a masterpiece of his life and one of the greatest statements in the history of art and self-expression!

Own Gramophone or Vinyl Record Player?

Check out some of the best recording of Schubert’s Piano Sonata no. 21!Alfred Brandel – a Chezch born Austrian pianists and musicologist. One of the most reowned pianists, famous for his Schubert, Beethoven and Mozart.

Editor’s Note: Classical Echoes is neither a retailer nor a producer of the listed products. The recommendations provided are based solely on personal opinion and experience. If you make a purchase through this link, we will earn a commission.

Share this post

Related

Best Recordings Of Schubert’s Sonata no. 21

Editor’s Note: Classical Echoes is neither a retailer nor a producer of the listed products. The recommendations provided are based solely on personal opinion and experience. If you make a purchase through this link, we will earn a commission.

Share this post

© Classical Echoes 2024