Introduction

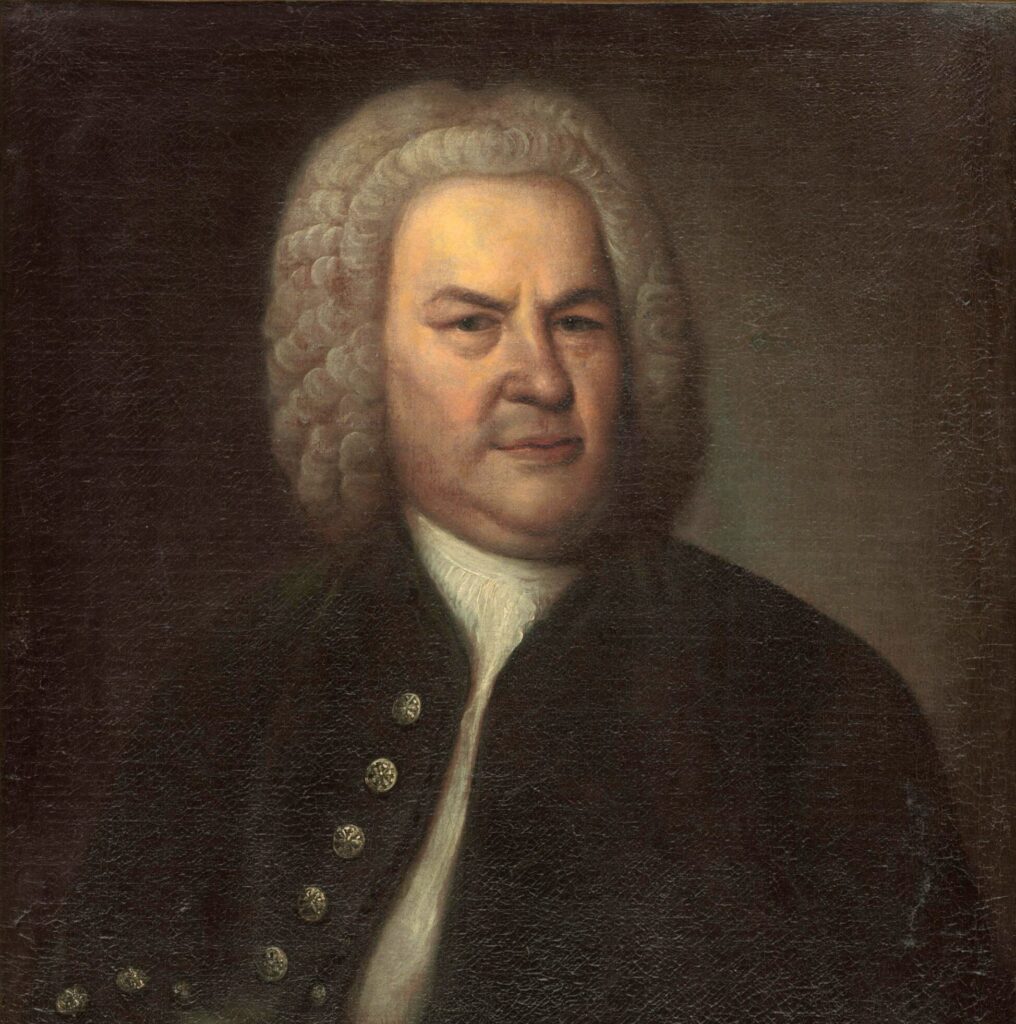

Bach — a grandaddy of fugues, a style that is one of the most crucial for music. Even though it was quite uncommon after Bach for classical composers to write fugues as separate pieces, it was still often included in many of their works. Take, for example, late Beethoven and his IV movement from Hammerklavier or the Ninth Symphony, or fugal entries in Mozart’s last symphony, one of the best examples of counterpoint in music.

Anyway, fugues play a crucial role in all classical music history, especially for composers. Writing a fugue is a common test for conservatory graduates and musical masters. For Bach, fugues were a significant part of his career, and he wrote many of them throughout his life. They are often considered perfect examples of combining several themes to create a counterpoint experience.

But what are some of the greatest of them? Which of Bach’s fugues are not only taught in music schools but are also famous for their beauty and complexity? Choosing the best examples of Bach’s fugues is the same as choosing the cream of the crop. So today, we’ll try to define Bach’s most celebrated, famous, and greatest fugues!

Fugue in C Sharp Minor

The fugue in C sharp minor from The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book One, is probably the most complex of his WTC series. It contains three themes and includes five voices. Some sections feature staccato parts, with all themes entering consecutively, overlapping, and creating stunning polyphony.

The main theme begins in the low baritone in the left hand and then repeats across five different voices. Accompanied by a countersubject, it flows into increasingly complex sounds, gradually introducing the remaining themes. Its culmination comes in the coda, bringing an intense polyphonic climax and resolving into a peaceful ending.

In terms of music, it is close to perfection. Its mathematical structure and counterpoint demonstrate Bach’s scientific approach. Famous Bach interpreter Glenn Gould called it “one of the most despairing and intense creations in the entire Well-Tempered Clavier.” Its emotional intensity and melancholic sound are truly impressive.

G. Gould – Fugue in C sharp minor WTC 1

Fugue in B Flat Minor

The B flat minor fugue is one of the cornerstone fugues in The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book Two. The fugue features four voices and one main theme, quite modest compared to the C sharp minor from WTC 1. However, its beauty lies not in complexity – a common attribute of Bach’s works – but in emotional meaning.

The first important aspect of this piece is its key. B flat minor is one of the coldest and darkest keys, rarely used during Bach’s time. The theme reflects this cold, sorrowful nature, creating a sad yet calm harmony. There is a particularly stunning sequence that flows into D flat major, changing the mood for a moment and creating a warming effect.

In this fugue, Bach focuses on emotional depth rather than technical and musical part. The piece profoundly expresses his feelings, contrary of the common misconception that WTC is purely a practical set of preludes and fugues.

S. Richter plays Fugue in B flat Minor from WTC 2 (yt. Pianoplayer002)

Related

The 11 Greatest Fugues Ever Written

How to Listen to Bach: A Beginner’s Guide

Confiteor

The Confiteor from Bach’s Mass in B Minor is one of the best non-solo piano fugues. It has a sacred religious meaning, as does the entire B Minor Mass. Thus, Bach, glorifying God in this music, included deep spiritual sense in this work.

This is a five-voice fugue with two main subjects. It opens with the words Confiteor unum baptisma (I confess one baptism for the forgiveness of sins), setting a calm and thoughtful tone. The second subject enters in reverse order, building more complex counterpoint. The fugue then transitions into a climactic ending that is not a fugue anymore but a triumphant finale, symbolizing the resurrection of Christ and Bach’s faith in God.

Bach – Confiteor from Mass in B Minor (yt.Deciphering Guitar and Music Theory)

Prelude and Fugue in A Minor

J. S. Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in A minor, BWV 543, is a set of two pieces originally written for the organ, likely composed in Weimar between 1708 and 1717. Similar to more famous works like the Toccata and Fugue in D minor, this piece didn’t receive much attention during Bach’s lifetime. However, like many of his masterpieces, it has been recognized posthumously as a stroke of genius.

The Prelude and Fugue in A Minor is an example of young Bach’s obsession with Italian Baroque music, particularly Vivaldi. The prelude is distinctly influenced by the Italian style, with its memorable, passionate, and mysterious theme. The fugue begins with a long, active subject, sharing similarities with another of Bach’s well-known fugues, the Little Fugue in G minor.

While the fugue in BWV 543 is a longer and more serious work, its beauty lies in its sequences and transitions between themes, as well as its elegant countersubjects. Today, this piece is regarded as one of Bach’s most famous early fugues and a example of his virtuosity. Later many composers, like Franz Liszt, transcribed it for piano, bringing it to a wider audience.

Bach/Liszt – Prelude and Fugue in A minor (yt. piano+)

Ricercar a 6

Ricercar a 6 is a six-voice fugue from The Musical Offering, BWV 1079. The Ricercar is an early Baroque term based on the Italian word “ricercare” — research. This is one of the most complex fugues and counterpoints in music. It is one of Bach’s late pieces, aimed to demonstrate all his compositional genius and mathematical perfection in music.

At the end of his life, Bach was considered to be the greatest musician alive, famous all across Europe among kings and courts. To prove his absolute musical genius, King Frederick challenged him to compose pieces based on his theme. Bach transformed a basic chromatic theme into series of masterpieces, the peak of which was his Ricercar a 6.

A single fugue for six voices, written for clavier, was demonstrated to the king by the aged Bach. This is now considered one of the most complex pieces in terms of music and composition techniques. Surely, it impressed the daring king and confirmed Bach’s title as the greatest composer of the Baroque era.

Ricercar a 6 (Netherland Bach Society)

Art of Fugue

The final major work by Bach was dedicated to fugues. The fugue was probably the most important musical genre for Bach in his life. The key idea of his music lies in its contrapuntal structure and dialogue between two themes that create a common sense together. Even though his final work, Art of Fugue, is often viewed as no more than a purely educational set of fugues, it is, in fact, the opposite. As with WTC, Art of Fugue is a much more profound and personal piece – final thoughts of a great composer. We will take a look at three of the greatest fugues in this set, defining the greatest fugue by Bach.

Contrapunctus VIII

The 8th contrapunctus of The Art of Fugue is a 3-voice triple-subject fugue with three differentiated themes. The first theme is based on the inversion of the main theme of the Art of Fugue. A dark D minor tune with a similarly striking accompaniment is introduced at the beginning of the fugue and slowly develops into a complex three-voice counterpoint.

After a lengthy and calm opening, there doesn’t seem to be much space for the development of the first theme, and here the genius of this fugue comes into play. At the end of the opening, Bach modulates into an unexpected chromatic sequence, a transition between two themes. In fact, the chromatic scale will become a main theme in the next two parts of the fugue.

As a result, the second theme consists of an upscaling theme accompanied by a more vivid and intense countersubject and sound. The polyphony becomes even more complex and passionate. The culmination of the whole fugue comes near its end, where Bach uses nearly every known technique of fugue writing and combines them into the most gentle and mathematically perfectly planned structured masterpiece, nearing the coda of the fugue. This transition from calm to intense is one of the hallmarks of Bach’s genius.

The fugue is longer than others in the set, making it one of the key turning points in The Art of Fugue, as Bach intended to make each fugue different and more complex than the previous one. In the eighth contrapunctus, he aimed to use not only his musical imagination but also to make some statements within the score, making this fugue one of the most passionate and genius works of his late period.

Contrapunctus VIII (yt. Ruoshi Sun)

Contrapunctus XIV (Unfinished)

The final contrapunctus in The Art of Fugue may be the most complex and greatest of the entire set. However, Bach left it unfinished, and it remains unknown whether he did so on purpose or not. As we know, he became blind due to an unsuccessful eye operation at the end of his life and couldn’t continue working on his scores. Nevertheless, even unfinished, it remains one of the most fascinating pieces in the set.

Generally speaking, some scholars believe that this fugue wasn’t originally part of the Art of Fugue but rather a separate piece. Interestingly, this is the only fugue that doesn’t contain the original D minor theme. Even so, G. Nottebohm demonstrated in his article that the theme of Contrapunctus 14 can be combined with the other main themes of The Art of Fugue, making it undoubtedly the most extraordinary of all.

This is the only quadruple fugue, and it amazes with its musical perfection. Here, Bach achieves absolute mastery of composition and explores the deepest corners of his imagination. The most touching part is its ending, where the entire musical universe suddenly stops in the most unexpected place, leaving behind only a long and uncertain silence.

This fugue is so unprecedented that it has become one of the greatest musical mysteries. Musicians from different generations have tried to recreate the fourth, unfinished section of the fugue based on Bach’s earlier works. However, these attempts were unsuccessful, as Contrapunctus 14 is so unique and unparalleled.

The previously mentioned pianist and Bach interpreter Glenn Gould said about this piece, “This is music that touches me more deeply than anything else I have ever encountered.”. Overall, this could very well be the greatest fugue of all time.

G. Gould obsesses over Contrapunctus 14 (yt. Music Video Vault)

Contrapunctus XI

Finally, we came to the greatest fugue within The Art of Fugue, and subsequently the greatest fugue by Bach – Contrapunctus XI. This four-voice triple fugue is an inversion of Contrapunctus VIII, but even more complex and interesting. This is the final fugue before the sequence of canons in the set, so Bach combined the best qualities of the previous ten in this particular fugue.

As mentioned, the three themes are basically inversions of themes from Contrapunctus VIII, but here Bach builds more complex development and countersubjects. The first “movement” is actually the inversion of the main theme, which has a similar mood to the first part of the eighth fugue.

After this, the chromatic theme is introduced, and we hear one of the most colorful and complex counterpoints in music. Bach builds more and more intense polyphony and makes the basic chromatic theme sound like a whole symphony, using only one keyboard, four voices, and some of Bach’s genius.

Contrapunctus XI is definitely astonishing in terms of music and self-expression. The work is so complex and unusual for Bach’s era that it’s hard to grasp it from just a single listening. The more you listen to Bach’s music, the more fascinating things you find about it!

J. MacGregor performs Contrapunctus XI